#l'état civil reconstitué

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I searched up Adrienne's name and on wikipedia her death date is listed as December 25th. Wasn't her death date the 24th or I misremembered the date right now? 'Cause didn't she died at the same day as Georges' birth, that was Dec. 24th?

Dear @msrandonstuff,

that is a very good question because both dates are sometimes wrongly given, and this matter caused me more than one headache when I first started focusing on the La Fayette’s.

In very short, Adrienne died on her sons 28th birthday, the 24th of December 1807.

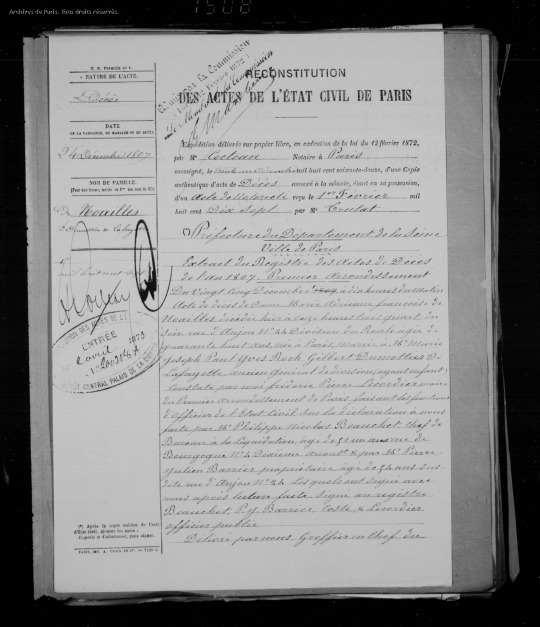

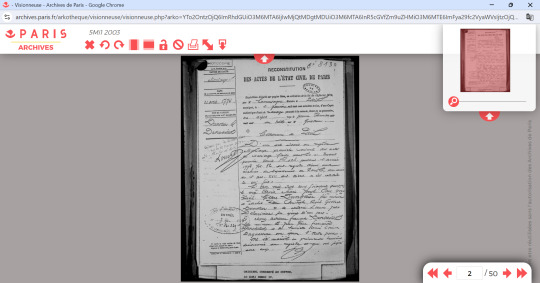

The best proof we have is the official registration of Adrienne’s death. The original document has been destroyed (with many, many more documents) but there is a reconstruction of the document.

In the top left-hand corner, we can read the date of death as “24 Décembre 1807”. In the main text we can read that the death was registered on December 25, but that Adrienne died “hier” meaning “yesterday”.

This official document should be enough to secure the date, but on top of that we also have a letter from La Fayette to his dear friend La Tour-Mauburg, written throughout January of 1808:

Another time she [Adrienne] fell into an ecstasy of joy at the thought of an anniversary dear to our hearts, of the day when, twenty-eight years before, she had given me George. That anniversary was the day of her death.

Mme de Lasteyrie, Life of Madame de Lafayette, L. Techener, London, 1872, p. 414.

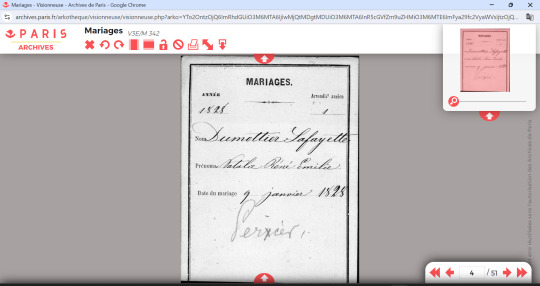

Here is Georges’ Acte de Naissance to verify the date.

We also have a quote from Jules Cloquet Germain’s book. Germain was a close family friend and La Fayette’s physician. He certainly knew when Adrienne died.

She was a model of heroism, and likewise of every virtue. During her captivity and her misfortunes, her blood imbibed the poison which, after protracted sufferings, terminated her existence on the 24th December, 1807.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 211.

You see, we have official documentation and the accounts from close family members. The only accounts that differ slightly, is from Adrienne’s sister Pauline. Her Memoirs suggest at one point the 25th (technically the 26th, because Pauline says that Adrienne died fifteen minutes past midnight) and a few pages later it reads as if Adrienne died on the 24th.

So why all this confusion? First if all, the English Wikipedia entry that you mentioned is the only one to give the 25th as the day she died. The French, Spanish and Simple English version for example all cite the 24th. In this case, it probably was just a mistake, a typo or something along the line. We see something similar in one of the earliest and most readily available English translations of Life of Madame de Lafayette. Here, Georges’ birthday is given as the 23rd of December 1779 while the French original clearly states the 24th. In other words, mistakes, in the process of translating and in the process of printing, do happen. Another problem is, that many sources give Adrienne’s day of death simply as “Christmas” without a specific date. Different cultures celebrate Christmas on different days and even within the same culture there may be different practices and/or changes over time.

In France for example, the 25th of December is a public holiday, and more and more families have their main Christmas celebrations on this day while other still celebrate on the more “traditional” 24th. Many families also celebrate on both days and meet with one part of the family on the 24th and with the other on the 25th. In Germany, as another example, the 25th and the 26th are public holidays (the first and the second Christmas day) but most families will have their main celebration and gift-giving on the 24th (that is no public holiday.)

These are my two cents on why there is sometimes confusion but also the answer to when Adrienne actually died. I hope you have/had a gorgeous day!

#ask me anything#msrandonstuff#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#christmas#1807#1808#letters#quote#georges washington de lafayette#jules germain cloquet#la tour-maubourg#marquise de montague#virginie de lafayette#l'état civil reconstitué

17 notes

·

View notes

Link

La révolte déclenchée par les jeunes Algériens a rapidement été amplifiée par la mobilisation, à leurs côtés, de leurs aînés. Cette génération, qui a connu la révolte d'octobre 1988, l'ouverture politique puis la guerre civile des années 1990, vit avec une intense émotion les événements de 2019.

Alger

Ammar Bouras a ressorti son Nikon. Les boulevards haussmanniens d'Alger-Centre, noirs de monde, le flou rouge-vert-blanc des drapeaux qui virevoltent, les regards fatigués des policiers sous leur casque bleu sont pour lui une matière enthousiasmante. Cela faisait bien longtemps que l'artiste plasticien, 54 ans, connu pour ses installations contemporaines, n'avait pas photographié l'actualité. Presque trente ans, en fait. Ses clichés argentiques en noir et blanc de l'Algérie des années 1990 (les défilés du Front islamique du salut, le président Mohammed Boudiaf quelques secondes avant son assassinat, le premier tour des élections législatives dans une école d'Alger…) justement réunis dans un beau livre qui vient de sortir aux prestigieuses éditions Barzakh, à Alger, se regardent comme une page en train de se tourner.

» LIRE AUSSI - Les impressionnantes images de la mobilisation contre Bouteflika

Une parenthèse est en train de se fermer. «Celle de la sortie de guerre», relève Malika Rahal, historienne à l'Institut d'histoire du temps présent, au CNRS, à Paris. Depuis quelques années, elle observe dans la société algérienne les signes discrets d'une renaissance, d'un plaisir et d'une fierté de l'action collective retrouvés. «On sort d'une époque où on résistait encore au fait d'être ensemble.» Il y a notamment, pour cette «génération 88», celle qui a connu la révolte d'octobre de cette année-là, l'ouverture politique puis la guerre civile des années 1990, «une libération du corps et de l'esprit, un allègement», note-t-elle. «Ça ne préjuge en rien de ce qui peut se passer. C'est de la joie toute nue.»

«Le drapeau incarnait tout ce que nous rejetions, le faux nationalisme qui bridait les gens. Peut-être qu'on est en train de se le réapproprier, ce drapeau, de dire qu'il est à nous ?»

Mouna, 52 ans, prof de lettres

Depuis le début de la mobilisation contre le cinquième mandat, le 22 février, la jeunesse qui s'est brusquement révoltée contre le système, que l'on dit peu concernée par les violences des années de terrorisme dans lesquelles l'Algérie a sombré en 1992, capte toute l'attention. Mais dans les rues, il y a aussi les quadras et les quinquas qui «ont repris espoir», constate Ammar. «Je retrouve cette Algérie de 1988, des gens soudés par des idées, un désir de changement, qui, d'une certaine manière, disent à nouveau leur refus du parti unique.»

À la veille de l'acte III des manifestations, dans un salon algérois, alors que des amis se retrouvent pour partager leurs émotions, les souvenirs ressurgissent invariablement dans les discussions. «La différence, c'est qu'à l'époque nous ne sortions pas avec les drapeaux!, s'amuse Mouna, 52 ans, prof de lettres. Le drapeau incarnait tout ce que nous rejetions, le faux nationalisme qui bridait les gens. Peut-être qu'on est en train de se le réapproprier, ce drapeau, de dire qu'il est à nous?»

Adlène Meddi, 43 ans, journaliste et écrivain dont les trois romans policiers transpirent le traumatisme des années 1990, en est convaincu: «La mobilisation aujourd'hui est une continuité de notre printemps, de l'incroyable révolution qu'a connue le pays à la fin des années 1980, résultat d'une prise de conscience de la société et d'une partie du système de la nécessité d'ouvrir le pays. Comme aujourd'hui, tous les Algériens étaient dans la rue, refusant le fait accompli. Ce souffle a été interrompu par les ténèbres, la frigorification. Mais la nuit s'est terminée le 22 février.»

Et si ce ne sont pas ces quadras qui ont enclenché les manifestations, c'est bien, comme le rappelle sur France Inter l'écrivain Kamel Daoud, 48 ans, parce que «le régime a toujours su opérer sur deux traumatismes». Celui de l'époque coloniale et de la menace d'une intervention de la France, comme en Libye, et celui de la décennie noire. «L'équation qui consiste à dire “soit nous, soit le chaos” a beaucoup pesé sur les consciences de ma génération.»

» LIRE AUSSI - Abdelaziz Bouteflika, un président usé qui ne comprend plus son peuple

Inquiet du rapport de force qui est en train de se jouer dans la rue, le pouvoir appuie sur la menace comme il jouerait une dernière carte. «Nous nous devons d'appeler à la vigilance et à la prudence quant à une éventuelle infiltration de cette expression pacifique par une quelconque partie insidieuse, interne ou externe, qui pourrait, qu'Allah nous en préserve, susciter la fitna et provoquer le chaos avec tout ce qu'ils peuvent entraîner comme crises et malheurs», a prévenu un message attribué à Abdelaziz Bouteflika. «L'Algérie a payé le prix fort pour le recouvrement de son indépendance et sa liberté, et notre peuple a payé un lourd et douloureux tribut pour en préserver l'unité et le rétablissement de sa paix et stabilité, après une tragédie nationale sanglante», a souligné le chef de l'État en appelant «les mères à veiller à la préservation de l'Algérie, en général, et de ses enfants en particulier».

« Je culpabilise quand je vois cette génération qui a su faire ce que nous n'avons pas su faire parce que nous étions trop marqués par la guerre civile», regrette aussi Kamel Daoud. Plus indulgente, l'éditrice Selma Hellal, de la maison Barzakh, préfère voir en «Silmiya» («pacifique», en arabe), écrit sur les pancartes brandies depuis quinze jours, «une passerelle» entre cette jeune génération et celle qui l'a précédée. «Un peu comme si elle avait une conscience sourde du chaos des années 1990.»

« Je culpabilise quand je vois cette génération qui a su faire ce que nous n'avons pas su faire parce que nous étions trop marqués par la guerre civile»

Kamel Daoud

Le traumatisme n'a pas été verbalisé dans toutes les familles. Mais il s'est transmis malgré tout, et se lit dans le regard inquiet des parents qui savent leurs enfants dans la rue. «Ce “Silmiya” est brandi comme un bouclier, analyse encore Selma. Comme pour dire: “On ne sait rien exactement des exactions, des violences, de la sauvagerie de cette époque, mais on refuse tout ça.”»

Dans un texte publié dans le quotidien El Watan, la sociologue Fatma Oussedik, qui analyse le profil démographique et sociologique des manifestants, remarque «une forte présence des classes moyennes habituellement silencieuses». «Ce sont ces avocats, ces médecins, ces enseignants qui ont 40 à 50 ans», précise-t-elle. «Cette classe moyenne, laminée pendant les années 1990, ciblée par des assassinats dont les auteurs n'ont jamais été retrouvés, s'est reconstituée et a mué pendant que le pouvoir, qu'elle considère comme un ennemi de classe, ne bougeait pas.» Bahia Bencheikh El Fegoun, 41 ans, illustre parfaitement son propos. Son documentaire prémonitoire, Fragments de rêves, qui donne la parole aux acteurs et leaders des mouvements sociaux en Algérie depuis 2011, a été censuré par le ministère de la Culture aux Rencontres cinématographiques de Béjaïa. Heureuse qu'il trouve aujourd'hui toute sa place dans le cours de l'histoire, la réalisatrice préfère parler de «réparation» plutôt que de «renaissance». «Chaque fois que je marche au milieu des manifestants, je ne peux pas m'empêcher de penser que nous sommes en train de réparer ce désamour que nous avions de nous-mêmes. Mais je n'ai jamais perdu la foi. Je n'ai jamais baissé les bras. Quand j'ai fait ce film, j'étais même en quête de révolution, et je peux vous dire que pour nous, Algériens, la révolution est un héritage très lourd! Aujourd'hui, je ne dirais pas que mon rêve se réalise. Il se met en route…»

Cette réparation, chacun la vit à sa façon. Vendredi matin, Ammar et sa femme se préparent à partir à la manifestation. « Avec notre voisine, on s'est organisés. J'ai acheté les drapeaux, elle nous a ramené des tee-shirts où est écrit “Non au cinquième mandat!” », explique-t-il en pensant, comme tous les Algérois qui s'apprêtent à «descendre à Alger», à l'itinéraire à emprunter et à l'endroit où stationner. «Bien sûr, je me demande ce qui va se passer après, aux lendemains, confie-t-il. Mais je veux profiter de l'instant. Parce que ce que je vois, c'est cette envie d'être ensemble. De faire quelque chose ensemble.»

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Guide to La Fayette’s Papers: Paris Archives

The Paris Archives are a true treasure trove for all sort of things and since so many liked the guide to the Archives of Seine-et-Marne, I wanted to give a little tour of the Paris Archives for everyone who might need it. I will be focusing on the official documents like certificate of birth, marriage and death.

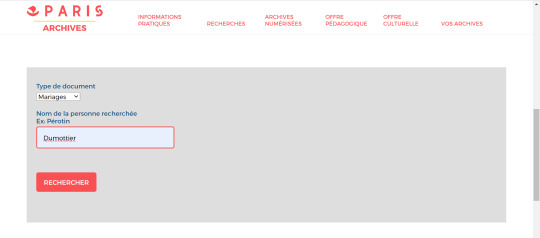

So first, we go to the webpage of the Paris Archives.

Next, we go to the section Archives Numérisées.

Once there you can actually access the Paris Archives own guide further down on the page.

But we are mainly here for the État civil de Paris, the very first box on the page.

We are scrolling down to the end of the page and now need to know what we are even looking for. If we are looking for an event (birth, marriage or death) that happened up until 1859, we have to choose the État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859). For everything else, the État civil à partir de 1860 is just the thing for us. Most documents that are relevant for La Fayette and his immediate family are to be found in the État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859).

Onwards we move and can now choose between the Fichiers de l'état civil reconstitué or the Actes de l'état civil reconstitué. The Fichiers are basically the short, alphabetically sorted version of the Actes and in my opinion much easier to search, especially if we do not know exactly what we are looking for. They are also only one page and present only the most basic information in short without much detail. We start with the Fichiers here.

We can now enter the type of document we are looking for (death, marriage and birth, displayed in that order) and the name of the person we are looking for. Now, here is the reminder that La Fayette was the families title, the surname was du Motier – depending on the archive we are using, sometimes both title or surname will yield results, sometimes just the one or the other and sometimes you even need a very specific spelling. In the case of the Paris Archives, I found that Dumottier works best – but I encourage you to always do some fiddling.

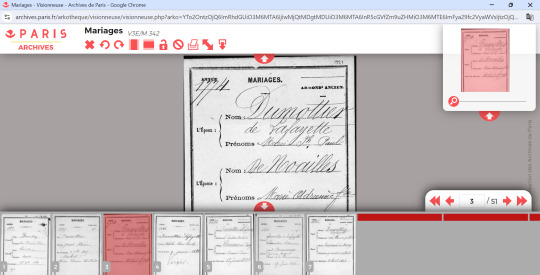

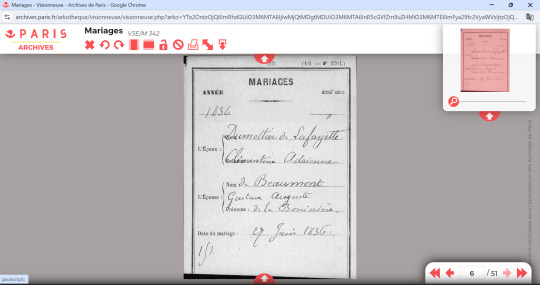

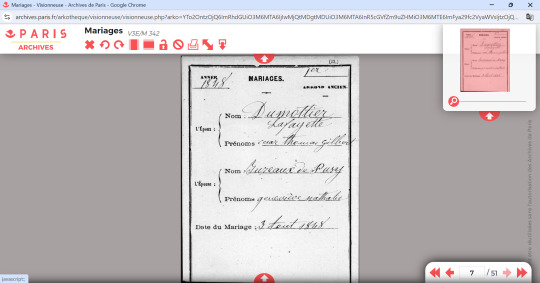

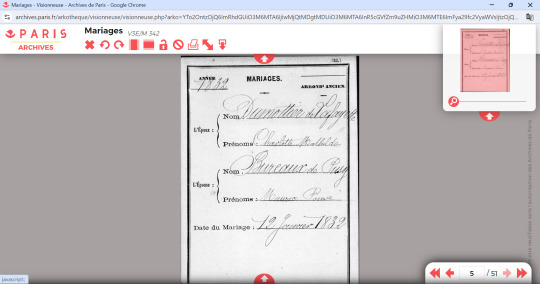

As you might have already guessed, we are looking for the certificate of marriage for Adrienne and La Fayette. These are our results:

With a click on the “eye” we can access the documents. They are indexed alphabetically and the first and last name found within the file is listed. If a name appears more than once, they are sorted by date.

As we can see, Fichiers only display the most important information, but they are easy to search … and look, the third entry is the certificate of Adrienne’s and La Fayette’s marriage that we were looking for. Now, the great thing about Fichiers is that they are sorted by name. Therefor, on pages four to seven we find the marriage certificates of Adrienne’s and La Fayette’s grandchildren.

With the symbol on the very right in the header we can download our finds as a PDF.

I really like that the Paris Archives mark which files have already been looked at by us.

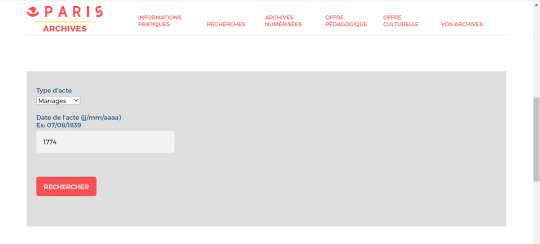

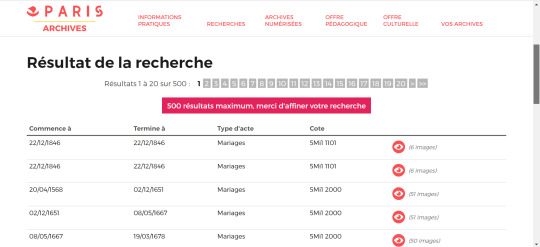

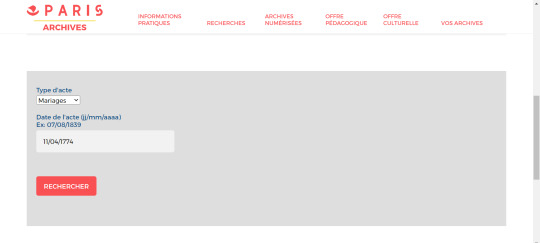

Now lets us have a look what happens when we choose the Actes and not the Fichiers.

We can again choose the type of document but search for a date now and not a name. The more precise we are, the better, since this happens, if we only know the year an event took place.

Now, with an exact date (a date we knew from the Fichiers) we find this:

I know that the La Fayette’s marriage certificate is split over both pf the two 5Mil 2003 files.

Et Voila! Happy researching!

#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#lafayette#french history#american history#history#archieve#paris archieves#resources#a guide to the lafayette papers

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! I don't know if anything is ever mentioned about that and it might be quite difficult to research, but I've been curious for a while about the fact that despite Georges de Lafayette's first name being spelled the French way on his État Civil and in various places, his family seem to consistently spell it like his namesake George Washington even in French. Moreover he is often named "George Washington de Lafayette" even though that middle name doesn't seem to have been official in any way.

I'm not entirely sure what the naming conventions were then, beside noble people often having a LOT of names (Lafayette more than most, but still), but if you have anything about Georges's name (I can think I know of one letter where Lafayette tells Washington about his namesake, but that's all that comes to mind), I'd love to see it!

Dear @echo-bleu,

I apologize that it took me so long to answer your question, but I had a lot of exams these past weeks – anyway – Georges and the spelling of his name, a source of endless frustration for me when I first got interested in him and his family.

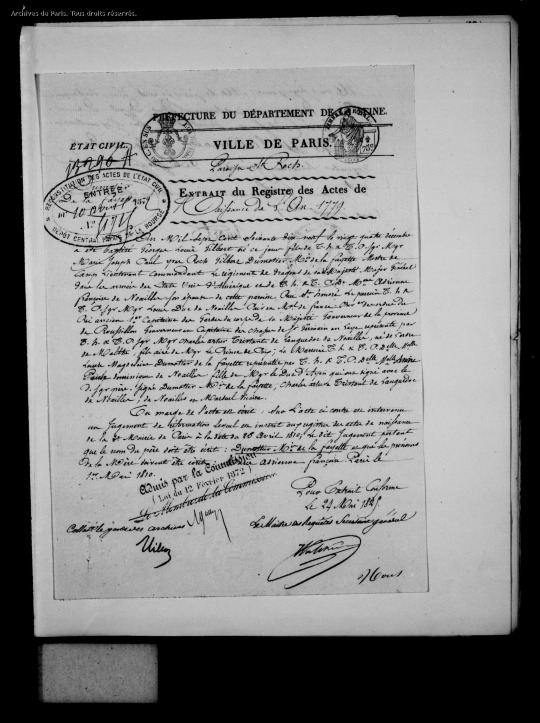

Here are my thoughts on the topic. First and foremost, George’s Extrait d’Acte de Naissance. As we can clearly see (and as you already said yourself) there is clearly an “s” but no “Washington” – basically the opposite of what we normally see where we have no “s” but a “Washington”.

La Fayette was always very adaptable when it came to spelling things – as we can see with his own name. He clearly preferred the English spelling of his son’s name, especially in English letters, but I also can not think of a single letter of his in French where he spells his sons name with the extra “s”. Though it should also be noted that a number of his letter were later anglicised. While there is today a clear trend to present his letters in the exact way he wrote them, some early biographers actually edited his original letters so that it is not always possible to go back to the original spelling. It may be possible that there were indeed letters where he added the “s” but that these letters are now lost to us. I think it is not extremely likely, but the possibility is out there. The naming of his son had always been indented as a homage to Washington and it is most likely that he wanted to emphasize this. I could also well imagine that his wife was a “cautioning” party when it came to the naming of their children. Maybe La Fayette had intended to spell his sons name “George” while Adrienne had advised to use the French spelling – an idea to which La Fayette agreed but was never fully committed. There are not many letters where Adrienne writes out the name of her son, but when she does, she actually uses both spellings. Most of the time it is “George” but there are also letters where she writes “Georges”.

Adrienne de La Fayette to George Washington, April 15, 1785:

wishing for so happy a moment, anastasie and Georges beg Leave, to send to the two youngest, miss Custis a toilett and a doll that is two play things with which my daughter is more delighted since two months, she is in possession of that she hopes, that her remembrance being some time mingled, with their entertainements, she may obtain some part in their frienship, whose she is so desirous of.

“To George Washington from Adrienne, Marquise de Lafayette, 15 April 1785,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series, vol. 2, 18 July 1784 – 18 May 1785, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1992, pp. 502–503.] (07/09/2022)

As to Georges himself, there are only a few letters where he spelled his name out. Most of the time he ended his letters with “G.W Lafayette” Here are two examples from different points in his life:

Georges W. de La Fayette to George Washington, December 21, 1797

George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: George Washington Motier Lafayette to George Washington. 1797. Manuscript/Mixed Material. (07/11/2022)

Georges W. de La Fayette to James Allyn, February 17, 1825

Lafayette Manuscripts, [Box 1, Folder 31], Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. (07/11/2022)

I know of two letters where is name is spelled out.

Georges W. de La Fayette to Monsieur Guittère, April 12, 1832

Archives départementales de Sein-et-Marne - La Fayette, une figure politique et agricole. (07/11/2022)

George W. de La Fayette to Andrew Jackson, June 15, 1834

Jackson, Andrew, and George Washington Lafayette. George Washington Lafayette to Andrew Jackson. 1834. Manuscript/Mixed Material. (07/11/2022)

Now, the second letter is only a copy, but assuming that the copy is made truthfully, we can see a tendency to use the English spelling on the few occasions he actually spelled his name out. It is also interesting to see how other people addressed him. In the political documents that I have seen it is always Georges with the “s” but almost always without the “W.” Close family friends such as Auguste Levasseur (La Fayette’s private secretary during and after his grand Tour of the United States) either opted for the “G. W.” or they spelled his name “George W.”

Auguste Levasseur to Georges W. de La Fayette, January 2, 1826:

Lafayette Manuscripts, [Box 1, Folder 32], Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. (07/11/2022)

Auguste Levasseur to Georges W. de La Fayette, undated (probably late 1826):

Lafayette Manuscripts, [Box 1, Folder 32], Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. (07/11/2022)

Where does this leave us? In short, I would say that while the “s” was an official part of his name, nobody in his family, Georges himself included, really paid it much mind and the English spelling was generally preferred. While Georges himself often used the “W” from “Washington” in his name, it appears to not have been an official part of his name. Furthermore, it appears that it was not noted as much back then then it is today. Today the alleged “Washington” part of his name is widely talked about while in his own time, there was not much more than the “W.” in his signature. I can not remember a single letter were either Adrienne or La Fayette specifically noted on the “Washington”. The emphasis then was always on the “George(s)”.

I hope that helped somewhat and I hope you have/had a gorgeous day!

#ask me anything#echo-bleu#georges washington de lafayette#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#adrienne de lafayette#auguste levasseur#captain francis allyn#letters#handwriting#founders online#library of congress#1826#1834#1832#1825#1797#1785#l'état civil reconstitué#1779

12 notes

·

View notes

Link

Depuis 2013, les militaires français se succèdent au Mali sous les opérations «Serval» ou «Barkhane». Pourtant la situation ne s'améliore pas entre des groupes terroristes qui s'adaptent à la présence française et un pays qui se délite en trois zones.

C'était le temps où François Hollande se promenait en libérateur dans les rues de Tombouctou. Dans la ville du Nord qui venait d'être reprise en un temps record par les forces françaises, l'ancien président avait déclaré, le 2 février: «Je viens de vivre la journée la plus importante de ma vie politique.» Il avait aussi fait une promesse: «La France restera avec vous le temps qu'il faudra.»

Lancée en janvier 2013 pour faire barrage aux djihadistes qui fonçaient sur la capitale Bamako, «Serval» fut un modèle d'intervention militaire. L'opération française a écarté en un temps record la menace des groupes armés islamistes. Dans la foulée, l'élection d'Ibrahim Boubakar Keïta (IBK) à la présidence faisait souffler dans la capitale un espoir de paix et de refondation démocratique pour le Mali. L'ouverture d'un dialogue avec le Nord, rebelle au pouvoir central de Bamako, laissait espérer une stabilisation de la zone sahélienne. Un an plus tard, le remplacement de «Serval» par «Barkhane», et ses 4500 soldats qui tentent de contenir la menace djihadiste dans la zone sahélienne, apportait un sérieux garde-fou régional contre la recrudescence du terrorisme.

Bamako dans un cocon

Cinq ans plus tard, l'optimisme a été balayé par les vents brûlants du désert. La communauté internationale est toujours au chevet d'un Mali qui part à la dérive et se délite en trois zones: le Nord qui échappe au contrôle de l'État, le Centre qui verse dans le chaos et le Sud, avec la capitale Bamako, qui vit dans un cocon et dans le déni. Malgré des centaines de millions d'euros d'aide et de perfusion financière, malgré les efforts des militaires français et des casques bleus de l'ONU, le pays est toujours au bord de l'implosion. Les pressions militaires et politiques n'ont pas permis de tracer un chemin vers la paix en imposant une solution politique entre le Nord irrédentiste et le Sud victime de l'incurie de ses dirigeants.

«C'est là, au centre du pays où se multiplient les violences et les attentats, que se joue en grande partie l'avenir du Mali»

La menace djihadiste, si elle a changé de forme, n'a pas disparu. Les groupes se sont reconstitués. Ils se sont adaptés à la présence française et à celle des Casques bleus. Ils s'enracinent dans les villages, remplissent le vide laissé par les services de l'État. Après les Arabes et les Touaregs du Nord, ils pénètrent désormais les populations peules. Le centre du pays est secoué par des tensions communautaires.

Les groupes armés y imposent leurs lois, y commettent des attentats, y exercent la pression djihadiste. La plupart des écoles ont été fermées, remplacées par des établissements coraniques réservés aux garçons d'où «jamais ne s'échappe un cri d'enfant», observe un officier général qui en revient. «C'est là, au centre du pays où se multiplient les violences et les attentats, que se joue en grande partie l'avenir du Mali», prévient-il. Mois après mois, la violence éclabousse les pays voisins, notamment le Niger et le Burkina Faso.

Principale opération extérieure française, «Barkhane» doit surveiller une région grande comme l'Europe, au nord du Mali ainsi qu'au-delà du fleuve Niger. À moyen terme, Paris mise sur le G5 Sahel, force militaire conjointe des pays de la région - Mauritanie, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger et Tchad - pour prendre le relais des soldats de «Barkhane». On n'en est pas encore là: le financement international de la force n'est toujours pas bouclé.

Quant à l'armée malienne, elle n'a pas résolu ses défaillances et rechigne toujours à investir les zones où grouillent les djihadistes, au nord de Bamako. Corrompue, sous-équipée, mal dirigée, minée par les désertions et par les conflits interethniques, divisée entre la hiérarchie et les soldats, elle est incapable de prendre le relais des forces françaises et de l'ONU. Pas davantage au Mali qu'en Afghanistan, le pari occidental de passer le relais aux forces locales n'a fonctionné.

Un plan de développement est nécessaire

À qui la faute? Au précédent gouvernement français qui a sans doute organisé des élections présidentielles trop tôt et poussé trop fort son protégé IBK, au nom des liens sacrés noués sur les bancs de l'Internationale socialiste? Au président malien, corrompu et incapable de restaurer l'autorité de l'État au nord et au centre du pays, qui a détourné l'argent prévu pour la reconstruction? À l'ambiguïté de la politique menée par les acteurs régionaux, notamment l'Algérie? En tout cas, pas aux militaires français. Dès les premiers jours de l'opération «Serval», ils avaient prévenu qu'il est toujours plus facile de gagner une guerre que de gagner la paix. Depuis, ils n'ont cessé de dire que l'action miliaire, pour qu'elle soit efficace, devait être couplée à un vaste plan de développement.

Le destin du Mali ressemble aujourd'hui à celui de l'Afghanistan, où les forces françaises ont épaulé les Américains: un succès militaire, une reconstruction jamais enclenchée et finalement la reconstitution d'une insurrection armée, encore plus aguerrie qu'avant. On ne voit pas comment la réélection d'IBK qui, selon un diplomate occidental, «jouit du pouvoir plus qu'il ne l'exerce», changerait la donne. Surtout dans un pays comme le Mali, qui demeure un empilage d'empires qui, du nord au sud, se haïssent profondément. «Aujourd'hui, notre marge de manœuvre est faible. Notre principal but, c'est de limiter les dégâts», commente un officier qui a servi au Mali.

Le risque, pour les forces françaises, mais aussi pour les Casques bleus de l'ONU, qui payent un lourd tribut à la mission de paix, est celui d'un enlisement dans un conflit sans fin. Mais sous peine d'abandonner un champ de bataille devenu stratégique, celui de la lutte antiterroriste, ni la France ni la communauté internationale ne peuvent lâcher le Mali.

De «Serval» à «Barkhane»

Après le lancement, le 11 janvier 2013 au Mali, de l'opération «Serval», avec 1700 soldats, la France a déployé l'opération «Barkhane» à compter d'août 2014, qui, elle, couvre, avec 4500 soldats, les cinq pays du Sahel. Au total, 22 soldats français ont été tués lors de ces deux opérations, dix avec Serval, douze avec Barkhane.

La Mission multidimensionnelle intégrée des Nations unies pour la stabilisation au Mali (Minusma) s'est déployée à partir du 1er juillet 2013, prenant le relais de la Mission internationale de soutien au Mali (Misma), formée par la Communauté économique des États d'Afrique de l'Ouest (Cedeao). La Minusma, avec un effectif de 15.000 personnes (12.169 militaires, 1 741 policiers, 1180 civils), est l'une des missions les plus importantes de l'ONU. Elle a perdu 170 Casques bleus. En 2015, les dirigeants du G5 Sahel (Mauritanie, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso et Tchad) décident de créer une force conjointe, mais elle peine à se déployer.

0 notes

Note

Thank you very much for the addition @echo-bleu! I must have skipped right past the document. :-) Although I am slowly getting better at finding what I am looking for in the Parisian archives … thanks to yours guidance.

And yes, La Fayette and Ségur were close enough that he was informed.

Hello dear,

I have a question that I hope isn’t too off topic or has already been asked.

I am currently reading through Adrienne de Lafayette’s bio by André Maurois and he keeps referencing the Marquis’ friend Ségur. I recall this name from other Lafayette biographies I have read but there I encountered the same problem. Does he have a title or a first name? It appears his father was a well respected general? But I can’t seem to piece together who that family is or what their standing was. I would love to know more about him, maybe dig into some correspondence as that is my one true vice. 😆 I just thought I would ask the Oracle since I’m stumped. 🤓😁

Well my dear @aconflagrationofmyown, I think I can help you with that. :-)

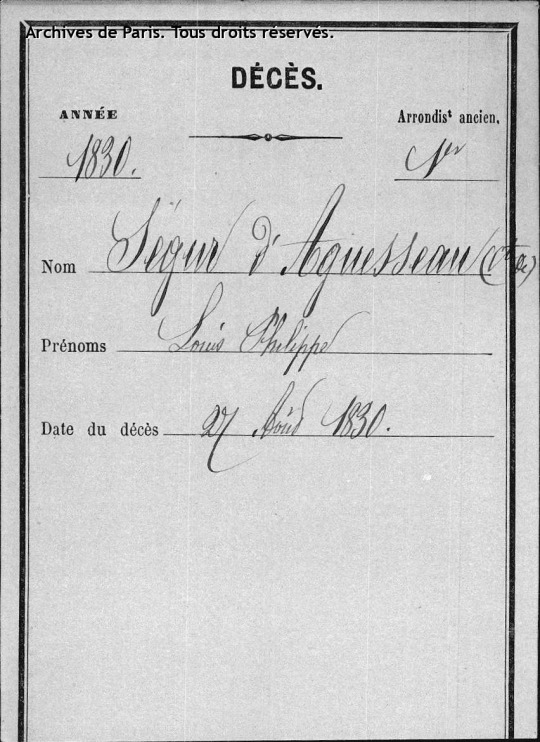

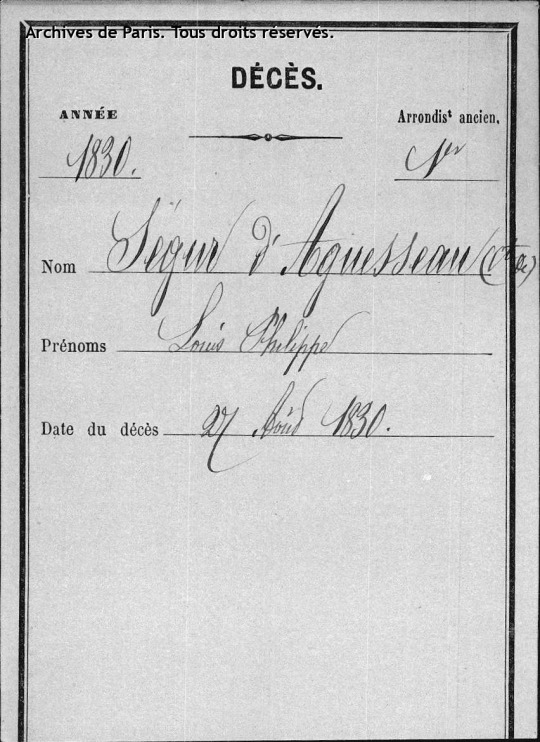

Yes, this mysterious Ségur has a name and a title. The “Ségur in question” was Louis Phlippe, comte de Ségur, born on December 10, 1753 in Paris and died on August 27, 1830 in Paris. He published his Memoirs and they are really worthwhile to read - interesting stories about a young La Fayette, insights into the inner circles of the French court at the time and of course into Ségur’s personal life. Here is his description of his relationship with La Fayette:

The three Frenchmen, distinguished by their rank at court, who first offered their military services to the Americans , were the Marquis de La Fayette, the Viscount de Noailles, and myself. We had long been intimate friends, and our connexion, which was strengthened by a great conformity of opinions, was soon after confirmed by the ties of blood.: La Fayette and the Viscount de Noailles had married two daughters of the Duke de Noailles, then bearing the title of Duke d'Ayen; their mother, the Dutchess d’Ayen, was the daughter, by his first marriage, of M. d'Aguesseau, Counsellor of State; and son of the Chancellor of that name M. d'Agur esseau had, by a second wife, twenty years after, several children, one of whom was M. d'Aguesseau, now a peer of France, a daughter, married to M. de Saron, first President of the Parliament of Paris, and another daughter, to whom I was united in the spring of 1777; so that, by this alliance, I became the uncle of my two friends.

Comte de Ségur, Memoirs and Recollections of the Count Segur, Ambassador from France to the Courts of Russia and Prussia, &c. &c., Wells and Lilly, Boston, 1825, p. 84.

Ségur’s descriptions of family relations is as confusing as it could possibly be and therefor once more in simple terms. La Fayette’s wife Adrienne had an aunt, her mother’s younger sister Antoinette-Elizabeth-Marie d’Aguesseau. This sister married Louis Philippe, comte de Ségur in 1777 in Paris and the couple had four children, three sons and one daughter. Ségur therefor was La Fayette’s uncle by marriage. Here is an example of how La Fayette described Ségur and their relationship. He wrote to George Washington on April 12, 1782:

This letter, My Dear General, Is Intrusted to Count de Segur, the Eldest Son of the Marquis de Segur Minister of State and of the War Departement Which in France Has a Great Importance—Count de Segur Was Soon Going to Have a Regiment, But He Prefers Serving in America, and Under Your orders—He is one of the Most Amiable, Sensible, and Good Natured Men I Ever Saw—He is My Very Intimate friend—I Recommend Him to You, My dear General, and through You to Every Body in America Particularly in the Army.

“To George Washington from Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, 12 April 1782,” Founders Online, National Archives, [This is an Early Access document from The Papers of George Washington. It is not an authoritative final version.] (05/20/2022)

You said you have already done some digging on your own and I assume you came across Ségur’s Memoirs. I include some links just in case and for everybody else who might be interested. Ségur’s memoirs are normally split into three volumes.

Internet Archive, French original: Volume One - Volume Two - Volume Three

Internet Archive, English Translation: Volume One (they do not have any more volumes in English)

Google Books, English Translation: Volume One - Volume Two - Volume Three

Since Ségur also worked as a diplomat and historian, he authored quite a number of works. Here is a little overview of all of his freely accessible books at the Internet Archive and via Google Books.

His second-oldest son, Phillipe-Paul also wrote his memoirs: An aide-de-camp of Napoleon. Memoirs of General Count de Ségur, of the French academy, 1800-1812.

Ségur hailed from a very well situated family. His father was Philippe Henri, Marquis de Ségur, decorated general and later Secretary of State for War during the American Revolution. He was the grand-son of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, regent of the Kingdome of France, by Orléans’ illegitimate daughter Philippe Angélique de Froissy. Ségur also had a younger brother, Joseph Alexandre Pierre, vicomte de Ségur. It is rumoured that Joseph Alexandre Pierre was not the son of Phillippe Henri but had actually been fathered by his “fathers” friend, Pierre Victor, baron de Besenval de Brünstatt. To my knowledge that had never been officially proven though.

The État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859) should technically have Ségur’s Acte de Décès but I could not find it at first glance. I did find however the corresponding Fichier in the État civil reconstitué and maybe that is of interest for you as well. It is quite interesting to observe that Ségur’s last name is given as a combination of his and his wife’s name.

Paris Archives, Fichiers de l'état civil reconstitué, Cote V3E/D 1356, p. 21. (05/20/2022)

You also mentioned that you were interested in correspondences - in fact, you said that they are your one true vice and I can absolutely understand that. Under the cut (as not to bother everybody who is just casually scrolling) I include the one fully transcribed letter by Ségur that I have. There are also a couple of letters where I only have the dates and short summaries - just let me know if you are interested in them as well.

I hope you have/had a beautiful day!

The comte de Ségur to the Marquis de La Fayette

Rochefort, July 7, 1782

I received, my dear Lafayette, your friendly letter, and I was extremely touched. I love you madly and I cannot console myself that I am not traveling with you. You are going to play a very honorable role, and one that is very difficult to play. You will have to reconcile the French and American characters, deal tactfully with opposing interests, and fill the measure of your glory to overflowing by adding the olive branch to the laurel leaves. And you will even have to act against your own inclination by helping to put a definite end to the horrible scourge to which you owe your fame. I am very sorry not to be able to talk with you freely at the moment I most desire it. But letters are not safe enough, and I haven't anything to tell you but things I would not want to be read. I foresee that you are going to be more revolted than ever at English arrogance, stupid Spanish vanity, French inconsistency, and despotic ignorance. You will see that the cabinet tries one's patience as much as a battlefield, and that as many stupid things are done in a negotiation as in a campaign. You will see especially how essentials are sacrificed to form, and you will say more than once, “If chance had not made me one of the principal actors, I should certainly not stay in the theater.” But the more obstacles you encounter, the more merit you will gain. How could you not succeed in all you desire, for you have genius and good fortune. To have that is to have half again as much as it takes to be a great man. Farewell, my friend. I expect to leave the day after tomorrow, consoling myself rather philosophically for going two thousand leagues for nothing, but not consoling myself for not finding you in a place that I find full of your name and your deeds. I shall carry out all your commissions, and I shall point out the patriotic sacrifice you are making in temporarily exchanging your sword for a pen. I request that you love my wife, hug my children, take my place with my father, and join us as soon as you can to sound the charge or beat the farewell retreat.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 5, January 4, 1782‑December 29, 1785, Cornell University Press, 1981, p. 51.

#reblog#echo-bleu#l'état civil reconstitué#french history#comte de ségur#marquis de ségur#marquis de lafayette#la fayette

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

Here you go with the Acte de Décès! 27 August 1830

Paris Archives, Actes de l'état civil reconstitué, Cote 5Mi1 1233, p. 29-30. (05/26/2022)

The last letter is very interesting, I didn’t know Ségur tried to see Lafayette in Rochefort before he left!

Hello dear,

I have a question that I hope isn’t too off topic or has already been asked.

I am currently reading through Adrienne de Lafayette’s bio by André Maurois and he keeps referencing the Marquis’ friend Ségur. I recall this name from other Lafayette biographies I have read but there I encountered the same problem. Does he have a title or a first name? It appears his father was a well respected general? But I can’t seem to piece together who that family is or what their standing was. I would love to know more about him, maybe dig into some correspondence as that is my one true vice. 😆 I just thought I would ask the Oracle since I’m stumped. 🤓😁

Well my dear @aconflagrationofmyown, I think I can help you with that. :-)

Yes, this mysterious Ségur has a name and a title. The “Ségur in question” was Louis Phlippe, comte de Ségur, born on December 10, 1753 in Paris and died on August 27, 1830 in Paris. He published his Memoirs and they are really worthwhile to read - interesting stories about a young La Fayette, insights into the inner circles of the French court at the time and of course into Ségur’s personal life. Here is his description of his relationship with La Fayette:

The three Frenchmen, distinguished by their rank at court, who first offered their military services to the Americans , were the Marquis de La Fayette, the Viscount de Noailles, and myself. We had long been intimate friends, and our connexion, which was strengthened by a great conformity of opinions, was soon after confirmed by the ties of blood.: La Fayette and the Viscount de Noailles had married two daughters of the Duke de Noailles, then bearing the title of Duke d'Ayen; their mother, the Dutchess d’Ayen, was the daughter, by his first marriage, of M. d'Aguesseau, Counsellor of State; and son of the Chancellor of that name M. d'Agur esseau had, by a second wife, twenty years after, several children, one of whom was M. d'Aguesseau, now a peer of France, a daughter, married to M. de Saron, first President of the Parliament of Paris, and another daughter, to whom I was united in the spring of 1777; so that, by this alliance, I became the uncle of my two friends.

Comte de Ségur, Memoirs and Recollections of the Count Segur, Ambassador from France to the Courts of Russia and Prussia, &c. &c., Wells and Lilly, Boston, 1825, p. 84.

Ségur’s descriptions of family relations is as confusing as it could possibly be and therefor once more in simple terms. La Fayette’s wife Adrienne had an aunt, her mother’s younger sister Antoinette-Elizabeth-Marie d’Aguesseau. This sister married Louis Philippe, comte de Ségur in 1777 in Paris and the couple had four children, three sons and one daughter. Ségur therefor was La Fayette’s uncle by marriage. Here is an example of how La Fayette described Ségur and their relationship. He wrote to George Washington on April 12, 1782:

This letter, My Dear General, Is Intrusted to Count de Segur, the Eldest Son of the Marquis de Segur Minister of State and of the War Departement Which in France Has a Great Importance—Count de Segur Was Soon Going to Have a Regiment, But He Prefers Serving in America, and Under Your orders—He is one of the Most Amiable, Sensible, and Good Natured Men I Ever Saw—He is My Very Intimate friend—I Recommend Him to You, My dear General, and through You to Every Body in America Particularly in the Army.

“To George Washington from Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, 12 April 1782,” Founders Online, National Archives, [This is an Early Access document from The Papers of George Washington. It is not an authoritative final version.] (05/20/2022)

You said you have already done some digging on your own and I assume you came across Ségur’s Memoirs. I include some links just in case and for everybody else who might be interested. Ségur’s memoirs are normally split into three volumes.

Internet Archive, French original: Volume One - Volume Two - Volume Three

Internet Archive, English Translation: Volume One (they do not have any more volumes in English)

Google Books, English Translation: Volume One - Volume Two - Volume Three

Since Ségur also worked as a diplomat and historian, he authored quite a number of works. Here is a little overview of all of his freely accessible books at the Internet Archive and via Google Books.

His second-oldest son, Phillipe-Paul also wrote his memoirs: An aide-de-camp of Napoleon. Memoirs of General Count de Ségur, of the French academy, 1800-1812.

Ségur hailed from a very well situated family. His father was Philippe Henri, Marquis de Ségur, decorated general and later Secretary of State for War during the American Revolution. He was the grand-son of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, regent of the Kingdome of France, by Orléans’ illegitimate daughter Philippe Angélique de Froissy. Ségur also had a younger brother, Joseph Alexandre Pierre, vicomte de Ségur. It is rumoured that Joseph Alexandre Pierre was not the son of Phillippe Henri but had actually been fathered by his “fathers” friend, Pierre Victor, baron de Besenval de Brünstatt. To my knowledge that had never been officially proven though.

The État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859) should technically have Ségur’s Acte de Décès but I could not find it at first glance. I did find however the corresponding Fichier in the État civil reconstitué and maybe that is of interest for you as well. It is quite interesting to observe that Ségur’s last name is given as a combination of his and his wife’s name.

Paris Archives, Fichiers de l'état civil reconstitué, Cote V3E/D 1356, p. 21. (05/20/2022)

You also mentioned that you were interested in correspondences - in fact, you said that they are your one true vice and I can absolutely understand that. Under the cut (as not to bother everybody who is just casually scrolling) I include the one fully transcribed letter by Ségur that I have. There are also a couple of letters where I only have the dates and short summaries - just let me know if you are interested in them as well.

I hope you have/had a beautiful day!

The comte de Ségur to the Marquis de La Fayette

Rochefort, July 7, 1782

I received, my dear Lafayette, your friendly letter, and I was extremely touched. I love you madly and I cannot console myself that I am not traveling with you. You are going to play a very honorable role, and one that is very difficult to play. You will have to reconcile the French and American characters, deal tactfully with opposing interests, and fill the measure of your glory to overflowing by adding the olive branch to the laurel leaves. And you will even have to act against your own inclination by helping to put a definite end to the horrible scourge to which you owe your fame. I am very sorry not to be able to talk with you freely at the moment I most desire it. But letters are not safe enough, and I haven't anything to tell you but things I would not want to be read. I foresee that you are going to be more revolted than ever at English arrogance, stupid Spanish vanity, French inconsistency, and despotic ignorance. You will see that the cabinet tries one's patience as much as a battlefield, and that as many stupid things are done in a negotiation as in a campaign. You will see especially how essentials are sacrificed to form, and you will say more than once, “If chance had not made me one of the principal actors, I should certainly not stay in the theater.” But the more obstacles you encounter, the more merit you will gain. How could you not succeed in all you desire, for you have genius and good fortune. To have that is to have half again as much as it takes to be a great man. Farewell, my friend. I expect to leave the day after tomorrow, consoling myself rather philosophically for going two thousand leagues for nothing, but not consoling myself for not finding you in a place that I find full of your name and your deeds. I shall carry out all your commissions, and I shall point out the patriotic sacrifice you are making in temporarily exchanging your sword for a pen. I request that you love my wife, hug my children, take my place with my father, and join us as soon as you can to sound the charge or beat the farewell retreat.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 5, January 4, 1782‑December 29, 1785, Cornell University Press, 1981, p. 51.

19 notes

·

View notes